If you need a Doctor See a Doctor, If you need a Hospital, Go to a Hospital

Our Products: Micro Particle Silver-Ion Solution 32oz / 16oz

1/2 Gal /1 Gal Special Orders Available

An Energized Dietary Supplement and Immune Support

25ppm @ <.0010 microns

Colloidal Silver Health Benefits & Use |

22 Colloidal Silver Benefits For Dogs (How To Use And Best Option) |

|

|

|

Dr. Gus - LEGIT Colloidal Silver - 6 Health Benefits, How To Make Colloidal Silver and Its Contraindications |

|

Medical uses of silver From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Medical uses of silver

| Medical uses of silver | |

|---|---|

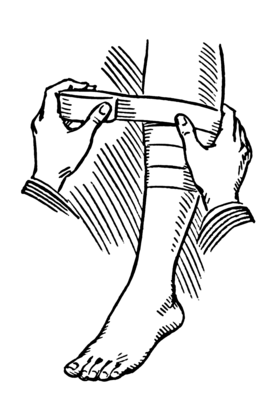

Silver is added to some bandages for its antimicrobial effect.

|

The medical uses of silver include its use in wound dressings, creams, and as an antibiotic coating on medical devices.[1][2] While wound dressings containing silver sulfadiazine or silver nanomaterials may be used on external infections,[3][4][5] there is little evidence to support such use.[6] There is tentative evidence that silver coatings on endotracheal breathing tubes may reduce the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia.[7]

Silver generally has low toxicity, and minimal risk is expected when silver is used in approved medical applications.[8] Alternative medicine products such as colloidal silver are not recognized as safe or effective by the FDA.[9]

Contents

Medical uses[edit]

Antibacterial cream[edit]

A 2012 systematic review reported that topical silver showed a significantly worsened healing time compared to controls and showed no evidence of effectiveness in preventing wound infection.[10] A 2010 Cochrane systematic review concluded: "There is insufficient evidence to establish whether silver-containing dressings or topical agents promote wound healing or prevent wound infection".[6]

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved a number of topical preparations of silver sulfadiazine for treatment of second- and third-degree burns.[11]

Dressings[edit]

A 2012 systematic review found that silver-containing dressings were no better than non-silver-containing dressings in treating burns.[10] A 2012 Cochrane review found that silver-containing hydrocolloid dressings were no better than standard alginate dressings in treating diabetic foot ulcers.[12] A 2010 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine if dressings containing silver increase or decrease infection or affect healing rates.[13] Another 2010 review found some evidence that silver-impregnated dressings improve the short-term healing of wounds and ulcers.[14] The lead author of this paper is a speaker for one of the manufacturers of one of the silver dressings under study.[14] A 2009 systematic review found that silver dressings improve both wound healing and quality of life when managing chronic non-healing wounds.[15] Another 2009 review concluded that the evidence for silver-containing foam in chronic infected wounds is not clear, but found that silver-containing foam resulted in a greater reduction in wound size and more effective control of leakage and odor than non-silver dressings.[16] A Cochrane review from 2013 found that all of the trials that assessed dressings on superficial and partial thickness burn wounds were at risk of bias and the data were poorly reported. Silver sulphadiazine had consistently poorer healing outcomes and delayed healing times compared with biosynthetic, silicon-coasted and silver dressings.[17] An earlier version of the review had raised concerns about delays in time to wound healing and an increased number of dressing applications when silver sulfadiazine (SSD) is used for the full duration of the treatment.[18] Another systematic review concluded that the evidence shows an overall positive effect of silver-releasing dressings in the management of infected chronic wounds, but expressed concern that the quality of the underlying trials was limited and potentially biased.[19]

A number of wound dressings containing silver as an anti-bacterial have been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[20][21][22][23]

Endotracheal tubes[edit]

Limited evidence suggests that endotracheal breathing tubes coated with silver may reduce the incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) and delay its onset, although no benefit is seen in the duration of intubation, the duration of stay in intensive care or the mortality rate.[7][24][25] Concerns have been raised surrounding the unblinded nature of some of the studies.[7] It is unknown if they are cost effective,[26] and more high quality scientific trials are needed.[25]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2007 cleared an endotracheal tube with a fine coat of silver to reduce the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.[27]

Catheters[edit]

Evidence does not support an important reduction in the risk of urinary tract infections when silver-alloy catheters are used.[28] These catheters are associated with greater cost than other catheters.[28]

Chlorhexidine-silver-sulfadiazine used in central venous catheters reduces the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections.[29]

X-ray film[edit]

Silver-halide imaging plates used with X-ray imaging were the standard before digital techniques arrived. Silver x-ray film remains popular for its accuracy, and cost effectiveness, particularly in developing countries, where digital X-ray technology is usually not available.[30]

Other uses[edit]

Silver compounds have been used in external preparations as antiseptics, including both silver nitrate and silver proteinate, which can be used in dilute solution as eyedrops to prevent conjunctivitis in newborn babies. Silver nitrate is also sometimes used in dermatology in solid stick form as a caustic ("lunar caustic") to treat certain skin conditions, such as corns and warts.[31] Silver is also used in bone prostheses, reconstructive orthopedic surgery and cardiac devices.[8]:17 Silver diamine fluoride appears to be an effective intervention to reduce dental caries (tooth decay).[32][33] Silver acetate has been used as a potential aid to help stop smoking; a review of the literature in 2012, however, found no effect of silver acetate on smoking cessation at a six-month endpoint and if there is an effect it would be small.[34] Silver has also been used in cosmetics, intended to enhance antimicrobial effects and the preservation of ingredients.[35]

Adverse effects[edit]

Though toxicity of silver is low, the human body has no biological use for silver and when inhaled, ingested, injected, or applied topically, silver will accumulate irreversibly in the body, particularly in the skin, and chronic use combined with exposure to sunlight can result in a disfiguring condition known as argyria in which the skin becomes blue or blue-gray.[8][36]:121 Localized argyria can occur as a result of topical use of silver-containing creams and solutions, while the ingestion, inhalation, or injection can result in generalized argyria.[37][38] Preliminary reports of treatment with laser therapy have been reported. These laser treatments are painful and general anesthesia is required.[39][40] A similar laser treatment has been used to clear silver particles from the eye, a condition related to argyria called argyrosis.[41] The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) describes argyria as a "cosmetic problem".[42]

One of the more publicized incidents of argyria came in 2008, when a man named Paul Karason, whose skin turned blue from using colloidal silver for over 10 years to treat dermatitis, appeared on NBC's "Today" show. Karason died in 2013 at the age of 62 after a heart attack.[43]

Colloidal silver may interact with some prescription medications, reducing the absorption of some antibiotics and thyroxine, among others.[44]

Some people are allergic to silver, and the use of treatments and medical devices containing silver is contraindicated for such people.[8] Although medical devices containing silver are widely used in hospitals, no thorough testing and standardization of these products has yet been undertaken.[45]

Water purification[edit]

Electrolytically-dissolved silver has been used as a water disinfecting agent, for example, the drinking water supplies of the Russian Mir orbital station and the International Space Station.[46] Many modern hospitals filter hot water through copper-silver filters to defeat MRSA and legionella infections.[47]:29 The World Health Organization includes silver in a colloidal state produced by electrolysis of silver electrodes in water, and colloidal silver in water filters as two of a number of water disinfection methods specified to provide safe drinking water in developing countries.[48] Along these lines, a ceramic filtration system coated with silver particles has been created by Ron Rivera of Potters for Peace and used in developing countries for water disinfection (in this application the silver inhibits microbial growth on the filter substrate, to prevent clogging, and does not directly disinfect the filtered water).[49][50][51]

Mechanism of action[edit]

Silver and most silver compounds have an oligodynamic effect and are toxic for bacteria, algae, and fungi in vitro. The antibacterial action of silver is dependent on the silver ion.[8] The effectiveness of silver compounds as an antiseptic is based on the ability of the biologically active silver ion (Ag+

) to irreversibly damage key enzyme systems in the cell membranes of pathogens.[8] The antibacterial action of silver has long been known to be enhanced by the presence of an electric field. Applying an electric current across silver electrodes enhances antibiotic action at the anode, likely due to the release of silver into the bacterial culture.[52] The antibacterial action of electrodes coated with silver nanostructures is greatly improved in the presence of an electric field.[53]

Silver, used as a topical antiseptic, is incorporated by bacteria it kills. Thus dead bacteria may be the source of silver which may kill additional bacteria.[54]

Alternative medicine [edit]

| Colloidal silver | |

|---|---|

A bottle of colloidal silver

|

|

| Alternative therapy | |

| Risks | Argyria, decreased drug absorption,[31] speculation that if bacteria become resistant to silver then that same resistance would apply to antibiotics[55] |

| Benefits | Placebo |

| Legality | Not to be sold for consumption or for disinfection in Sweden.[55][56] Not to treat or prevent cancer (UK, Sweden, etc.) |

Colloidal silver (a colloid consisting of silver particles suspended in liquid) and formulations containing silver salts were used by physicians in the early 20th century, but their use was largely discontinued in the 1940s following the development of safer and effective modern antibiotics.[36][57] Since about 1990, there has been a resurgence of the promotion of colloidal silver as a dietary supplement,[31] marketed with claims of it being an essential mineral supplement, or that it can prevent or treat numerous diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, herpes,[36] and tuberculosis.[31][58][59] No medical evidence supports the effectiveness of colloidal silver for any of these claimed indications.[31][60][61] Silver is not an essential mineral in humans; there is no dietary requirement for silver, and hence, no such thing as a silver "deficiency".[31] There is no evidence that colloidal silver treats or prevents any medical condition, and it can cause serious and potentially irreversible side effects such as argyria.[31]

In August 1999, the U.S. FDA banned colloidal silver sellers from claiming any therapeutic or preventive value for the product,[60] although silver-containing products continue to be promoted as dietary supplements in the U.S. under the looser regulatory standards applied to supplements.[60] The FDA has issued numerous Warning Letters to Internet sites that have continued to promote colloidal silver as an antibiotic or for other medical purposes.[62][63][64] Despite the efforts of the FDA, silver products remain widely available on the market today. A review of websites promoting nasal sprays containing colloidal silver suggested that information about silver-containing nasal sprays on the internet is misleading and inaccurate.[65]

In 2002, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) found there were no legitimate medical uses for colloidal silver and no evidence to support its marketing claims.[66] The U.S. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) warns that marketing claims about colloidal silver are scientifically unsupported, that the silver content of marketed supplements varies widely, and that colloidal silver products can have serious side effects such as argyria.[31] In 2009, the USFDA issued a "Consumer Advisory" warning about the potential adverse effects of colloidal silver, and said that "...there are no legally marketed prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs containing silver that are taken by mouth."[67] Quackwatch states that colloidal silver dietary supplements have not been found safe or effective for the treatment of any condition.[68] Consumer Reports lists colloidal silver as a "supplement to avoid", describing it as "likely unsafe".[69] The Los Angeles Times stated that "colloidal silver as a cure-all is a fraud with a long history, with quacks claiming it could cure cancer, AIDS, tuberculosis, diabetes, and numerous other diseases."[70]

It may be illegal to market as preventing or treating cancer, and in some jurisdictions illegal to sell colloidal silver for consumption.[55] In 2015 a British man was prosecuted and found guilty under the Cancer Act 1939 for selling colloidal silver with claims it could treat cancer.[71]

History[edit]

Hippocrates in his writings discussed the use of silver in wound care.[72] At the beginning of the twentieth century surgeons routinely used silver sutures to reduce the risk of infection.[72][73] In the early 20th century, physicians used silver-containing eyedrops to treat ophthalmic problems,[74] for various infections,[75][76] and sometimes internally for diseases such as tropical sprue, epilepsy, gonorrhea, and the common cold.[31][57][77] During World War I, soldiers used silver leaf to treat infected wounds.[72][78]

Prior to the introduction of modern antibiotics, colloidal silver was used as a germicide and disinfectant.[79] With the development of modern antibiotics in the 1940s, the use of silver as an antimicrobial agent diminished.[45] Silver sulfadiazine (SSD) is a compound containing silver and the antibiotic sodium sulfadiazine, which was developed in 1968.

Cost[edit]

The National Health Services in the UK spent about £25 million on silver-containing dressings in 2006. Silver-containing dressings represent about 14% of the total dressings used and about 25% of the overall wound dressing costs.[80]

Concerns have been expressed about the potential environmental cost of manufactured silver nanomaterials in consumer applications being released into the environment, for example that they may pose a threat to benign soil organisms.[81]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Maillard JY, Hartemann P (2013). "Silver as an antimicrobial: facts and gaps in knowledge". Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 39 (4): 373–83. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2012.713323. PMID 22928774.

- ^ Medici, Serenella; Peana, Massimiliano; Crisponi, Guido; Nurchi, Valeria M.; Lachowicz, Joanna I.; Remelli, Maurizio; Zoroddu, Maria Antonietta (November 2016). "Silver coordination compounds: A new horizon in medicine". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 327–328: 349–359. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2016.05.015.

- ^ Atiyeh BS, Costagliola M, Hayek SN, Dibo SA (2007). "Effect of silver on burn wound infection control and healing: review of the literature". Burns. 33 (2): 139–48. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2006.06.010. PMID 17137719.

- ^ Qin Y (2005). "Silver-containing alginate fibres and dressings". Int Wound J. 2 (2): 172–6. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4801.2005.00101.x. PMID 16722867.

- ^ Hermans MH (2006). "Silver-containing dressings and the need for evidence". Am J Nurs. 106 (12): 60–8; quiz 68–9. doi:10.1097/00000446-200612000-00025. PMID 17133010.

- ^ a b Storm-Versloot MN, Vos CG, Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H (2010). Storm-Versloot, Marja N, ed. "Topical silver for preventing wound infection". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006478. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006478.pub2. PMID 20238345.

- ^ a b c Bouadma L, Wolff M, Lucet JC (2012). "Ventilator-associated pneumonia and its prevention". Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 25 (4): 395–404. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328355a835. PMID 22744316.

- ^ a b c d e f Lansdown AB (2006). "Silver in health care: antimicrobial effects and safety in use". Curr. Probl. Dermatol. Current Problems in Dermatology. 33: 17–34. doi:10.1159/000093928. ISBN 3-8055-8121-1. PMID 16766878.

- ^ "Over-the-Counter Drug Products Containing Colloidal Silver Ingredients or Silver Salts". FDA. August 17, 1999. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b Aziz Z, Abu SF, Chong NJ (2012). "A systematic review of silver-containing dressings and topical silver agents (used with dressings) for burn wounds". Burns. 38 (3): 307–18. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2011.09.020. PMID 22030441.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA". Accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Dumville, JC; O'Meara, S; Deshpande, S; Speak, K (25 June 2013). "Alginate dressings for healing diabetic foot ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD009110. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009110.pub3. PMID 23799857.

- ^ Storm-Versloot MN, Vos CG, Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H (2010). "Topical silver for preventing wound infection". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006478. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006478.pub2. PMID 20238345.

- ^ a b Carter MJ, Tingley-Kelley K, Warriner RA (2010). "Silver treatments and silver-impregnated dressings for the healing of leg wounds and ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 63 (4): 668–79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.007. PMID 20471135.

- ^ Lo SF, Chang CJ, Hu WY, Hayter M, Chang YT (2009). "The effectiveness of silver-releasing dressings in the management of non-healing chronic wounds: a meta-analysis". J Clin Nurs. 18 (5): 716–28. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02534.x. PMID 19239539.

- ^ Beam JW (Sep–Oct 2009). "Topical silver for infected wounds". J Athl Train. 44 (5): 531–3. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-44.5.531. PMC 2742464

. PMID 19771293.

. PMID 19771293. - ^ Wasiak, J; Cleland, H; Campbell, F; Spinks, A (28 March 2013). "Dressings for superficial and partial thickness burns". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD002106. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002106.pub4. PMID 23543513.

- ^ Wasiak, J; Cleland, H; Campbell, F (8 October 2008). "Dressings for superficial and partial thickness burns". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD002106. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002106.pub3. PMID 18843629.

- ^ Lo SF, Hayter M, Chang CJ, Hu WY, Lee LL (2008). "A systematic review of silver-releasing dressings in the management of infected chronic wounds". J Clin Nurs. 17 (15): 1973–85. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02264.x. PMID 18705778.

- ^ Ethicon, Inc. 510(k) Summary for K022483 Feb. 3, 2003

- ^ Argentum Medical LLC 510(k) Summary for K023609 Jan 17, 2003

- ^ Euromed, Inc. 510(k) Summary for K050032 May 17, 2005

- ^ Kinetic Concepts, Inc. 510(k) Summary for K053627 Feb. 6, 2006

- ^ Hunter JD (2012). "Ventilator associated pneumonia". BMJ. 344: e3325. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3325. PMID 22645207.

- ^ a b Li X, Yuan Q, Wang L, Du L, Deng L (2012). "Silver-coated endotracheal tube versus non-coated endotracheal tube for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia among adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". J Evid Based Med. 5 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1111/j.1756-5391.2012.01165.x. PMID 23528117.

- ^ Kane T, Claman F (Sep 4–10, 2012). "Silver tube coatings in pneumonia prevention". Nurs Times. 108 (36): 21–3. PMID 23035371.

- ^ "FDA Clears Silver-Coated Breathing Tube For Marketing". 2007-11-08. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007.

- ^ a b Lam TB, Omar MI, Fisher E, Gillies K, MacLennan S (2014). "Types of indwelling urethral catheters for short-term catheterisation in hospitalised adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9 (9): CD004013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004013.pub4. PMID 25248140.

- ^ Coppin-Raynal, E; Le Coze, D (October 1982). "Mutations relieving hypersensitivity to paromomycin caused by ribosomal suppressors in Podospora anserina". Genetical research. 40 (2): 149–64. doi:10.1017/s0016672300019029. PMID 7152256.

- ^ Zennaro, F; Oliveira Gomes, J. A.; Casalino, A; Lonardi, M; Starc, M; Paoletti, P; Gobbo, D; Giusto, C; Not, T; Lazzerini, M (2013). "Digital radiology to improve the quality of care in countries with limited resources: A feasibility study from Angola". PLoS ONE. 8 (9): e73939. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073939. PMC 3783475

. PMID 24086301.

. PMID 24086301. - ^ a b c d e f g h i "Colloidal Silver" (Last Updated September 2014). National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Rosenblatt A, Stamford TC, Niederman R (2009). "Silver diamine fluoride: a caries "silver-fluoride bullet"". J. Dent. Res. 88 (2): 116–125. doi:10.1177/0022034508329406. PMID 19278981.

- ^ Deery C (2009). "Silver lining for caries cloud?". Evid Based Dent. 10 (3): 68. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400661. PMID 19820733.

- ^ Lancaster T, Stead LF (2012). "Silver acetate for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9 (9): CD000191. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000191.pub2. PMID 22972041.

- ^ Kokura, Satoshi, Osamu Handa, Tomohisa Takagi, Takeshi Ishikawa, Yuji Naito, and Toshikazu Yoshikawa (2010). "Silver nanoparticles as a safe preservative for use in cosmetics". Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 06 (4): 570–74. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2009.12.002.

- ^ a b c Fung MC, Bowen DL (1996). "Silver products for medical indications: risk-benefit assessment". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 34 (1): 119–126. doi:10.3109/15563659609020246. PMID 8632503.

- ^ Brandt D, Park B, Hoang M, Jacobe HT (2005). "Argyria secondary to ingestion of homemade silver solution". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 53 (2 Suppl 1): S105–7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.09.026. PMID 16021155.

- ^ Okan D, Woo K, Sibbald RG (2007). "So what if you are blue? Oral colloidal silver and argyria are out: safe dressings are in". Adv Skin Wound Care. 20 (6): 326–30. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000276415.91750.0f. PMID 17538258.

Colloidal silver suspensions are solutions of submicroscopic metallic silver particles suspended in a colloid base. These products deliver predominantly inactive metallic silver, not the antimicrobial ionized form.

- ^ Rhee DY, Chang SE, Lee MW, Choi JH, Moon KC, Koh JK (2008). "Treatment of argyria after colloidal silver ingestion using Q-switched 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser". Dermatol Surg. 34 (10): 1427–30. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34302.x. PMID 18657163.

- ^ Jacobs R (2006). "Argyria: my life story". Clin. Dermatol. 24 (1): 66–9; discussion 69. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.09.001. PMID 16427508.

- ^ Geyer O, Rothkoff L, Lazar M (1989). "Clearing of corneal argyrosis by YAG laser". Br J Ophthalmol. 73 (12): 1009–10. doi:10.1136/bjo.73.12.1009. PMC 1041957

. PMID 2611183.

. PMID 2611183. - ^ "ToxFAQs™ for Silver" (Page last updated: March 26, 2014). Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ^ Moran, Lee. (2013-09-25) Man who turned blue after taking silver for skin condition dies. Nydailynews.com. Retrieved on 2016-11-26.

- ^ Pamela L. Drake, M.P.H., National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety; Edmund Pribitkin, M.D., Thomas Jefferson University; and Wendy Weber, N.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., NCCIH (July 2009). "Colloidal Silver Products". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- ^ a b Chopra I (2007). "The increasing use of silver-based products as antimicrobial agents: a useful development or a cause for concern?". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59 (4): 587–90. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm006. PMID 17307768.

- ^ Subcommittee on Spacecraft Exposure Guidelines, Committee on Toxicology, National Research Council (2004). Spacecraft Water Exposure Guidelines for Selected Contaminants. 1. National Academies Press. p. 324. ISBN 0-309-09166-7.

- ^ Alan B. G. Lansdown (27 May 2010). Silver in Healthcare: Its Antimicrobial Efficacy and Safety in Use. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84973-006-8. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ Solsona, Felipe; Juan Pablo Mendez (2003). "Water Disinfection" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ^ Richmond, Caroline (2008-10-16). "Ron Rivera: Potter who developed a water filter that saved lives in the third world". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- ^ Corbett, Sara (December 24, 2008). "Solution in a Pot". New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ Committee on Creation of Science-based Industries in Developing Countries, Development, Security, and Cooperation, Policy and Global Affairs, National Research Council of the National Academies, Nigerian Academy of Science. (2007). Mobilizing Science-Based Enterprises for Energy, Water, and Medicines in Nigeria. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-309-11118-8.

- ^ Spadaro, J. A.; Berger, T. J.; Barranco, S. D.; Chapin, S. E.; Becker, R. O. (1974). "Antibacterial Effects of Silver Electrodes with Weak Direct Current". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 6 (5): 637–642. doi:10.1128/AAC.6.5.637. PMC 444706

. PMID 15825319.

. PMID 15825319. - ^ Akhavan, Omid; Ghaderi, Elham (2009). "Enhancement of antibacterial properties of Ag nanorods by electric field". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 10 (1): 015003. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/10/1/015003. PMC 5109610

. PMID 27877266.

. PMID 27877266. - ^ Wakshlak, Racheli Ben-Knaz; Pedahzur, Rami; Avnir, David (23 April 2015). "Antibacterial activity of silver-killed bacteria: the "zombies" effect". Scientific Reports. 5: article 9555. doi:10.1038/srep09555. PMID 25906433.

A mechanism is suggested in terms of the action of the dead bacteria as a reservoir of silver, which, due to Le-Chatelier's principle, is re-targeted to the living bacteria.

- ^ a b c "Kolloidalt silver" (Last updated Feb 17, 2016). Livsmedelsverket (Swedish Food Agency). Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ "Vad gäller om jag vill sälja kolloidalt silver som biocidprodukt?". Kemi (Swedish Chemicals Agency). Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Colloidal silver". Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. May 16, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ Wadhera A, Fung M (2005). "Systemic argyria associated with ingestion of colloidal silver". Dermatol. Online J. 11 (1): 12. PMID 15748553.

- ^ Fung MC, Weintraub M, Bowen DL (1995). "Colloidal silver proteins marketed as health supplements". JAMA. 274 (15): 1196–7. doi:10.1001/jama.274.15.1196. PMID 7563503.

- ^ a b c "Over-the-counter drug products containing colloidal silver ingredients or silver salts. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Public Health Service (PHS), Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Final rule" (PDF). Fed Regist. 64 (158): 44653–8. 1999. PMID 10558603.

- ^ Newman M, Kolecki P (2001). "Argyria in the ED". Am J Emerg Med. 19 (6): 525–6. doi:10.1053/ajem.2001.25773. PMID 11593479.

- ^ "Colloidal Silver Not Approved". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ^ "FDA Warning Letter" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2001-03-13. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ^ "FDA Warning Letter". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- ^ Gaslin MT, Rubin C, Pribitkin EA (2008). "Silver nasal sprays: misleading Internet marketing". Ear Nose Throat J. 87 (4): 217–20. PMID 18478796.

- ^ "Regulation of colloidal silver and related products". Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration. 2005-11-09. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ^ FDA Consumer Advisory (October 6, 2009). Dietary Supplements Containing Silver May Cause Permanent Discoloration of Skin and Mucous Membranes (Argyria).

- ^ Edward McSweegan. "Lyme Disease: Questionable Diagnosis and Treatment" (Revised on April 4, 2016.). Quackwatch. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ^ "Twelve supplements you should avoid". Consumer Reports. September 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Colker, David (May 2, 2009). "Scam 'cures' for swine flu face crackdown". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ "Man is fined after selling "cancer cure" which he made at home". Chelmsford Weekly News. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Dai T, Huang YY, Sharma SK, Hashmi JT, Kurup DB, Hamblin MR (2010). "Topical antimicrobials for burn wound infections". Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 5 (2): 124–151. doi:10.2174/157489110791233522. PMC 2935806

. PMID 20429870.

. PMID 20429870. - ^ Alexander JW (2009). "History of the medical use of silver". Surg Infect (Larchmt). 10 (3): 289–92. doi:10.1089/sur.2008.9941. PMID 19566416.

- ^ Roe AL (1915). "COLLOSOL ARGENTUM AND ITS OPHTHALMIC USES". Br Med J. 1 (2820): 104. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2820.104. PMC 2301624

. PMID 20767446.

. PMID 20767446. - ^ MacLeod, C (1912). "Electric metallic colloids and their therapeutic applications". Lancet. 179 (4614): 322–323. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)66545-0.

- ^ Searle, A.B. (1920). "Chapter IX: Colloidal Remedies and Their Uses". The Use of Colloids in Health and Disease. Gerstein-University of Toronto : Toronto Collection: London Constable & Co.

- ^ "Eighty-first Annual Meeting of the British Medical Association". BMJ. 2 (2759): 1282–1302. 1913. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2759.1282.

- ^ Borsuk DE, Gallant M, Richard D, Williams HB (2007). "Silver-coated nylon dressings for pediatric burn victims". Can J Plast Surg. 15 (1): 29–31. PMC 2686041

. PMID 19554127.

. PMID 19554127. - ^ Searle, A.B. (1920). "Chapter VIII: Germicides and Disinfectants". The Use of Colloids in Health and Disease. Gerstein – University of Toronto : Toronto Collection: London Constable & Co.

- ^ "Silver dressings—do they work?". Drug Ther Bull. 48 (4): 38–42. 2010. doi:10.1136/dtb.2010.02.0014. PMID 20392779.

- ^ Tolaymat TM, El Badawy AM, Genaidy A, Scheckel KG, Luxton TP, Suidan M (2010). "An evidence-based environmental perspective of manufactured silver nanoparticle in syntheses and applications: a systematic review and critical appraisal of peer-reviewed scientific papers". Sci. Total Environ. 408 (5): 999–1006. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.11.003. PMID 19945151.